Haven't lost the desire to blog. Was away much of August. Started back to work last week. Spent some time setting up my classroom. Here are some pics.

I know many of you have setups like this. For me, though, this is a big change. I have always worked in rooms with rows. For many years, I have 'floated' into other teachers' classrooms, where there were rows. And, for the past five years or so, I have been in this room, yet I have continued to keep the desks in rows.

Obviously, this is just a structural change, but a better arrangement of my space is a necessary prerequisite to more collaboration in my classroom. There is so much more that I want to change. I will keep sharing, as I implement various modifications.

Saturday, August 31, 2013

Wednesday, August 14, 2013

The SHEG Model of Lesson Plan, Part I

I'd like to spend some time thinking about an SHEG lesson, considering what it includes and excludes, as well as how its structure compares to the way I was taught to lesson plan (pdf).

No Stated Learning Objectives

As I've pointed out in some of my tweets, I think it is significant that the authors do not include a list of learning objectives. This stands out to me because it is contrary to the model of lesson planning that I was taught, and I am sure many of you were also, when taking education classes (pdf). I accept that there is more than one way to lesson plan, though I have rarely observed models that do not include learning objectives.

In fact, a style of lesson planning that purposely excludes defining learning objectives is, in my opinion, quite provocative and sending a clear and powerful message about one of its prime assumptions about teaching and learning.

The assumption that I detect is that it is not necessary for a teacher to state in precise language measurable statements about what a student will, and by implication, will not learn in a lesson. It is enough to base your lesson on a quality process and some meaningful content.

The SHEG model's quality process is, at its core, a genuine commitment to having students close read primary and secondary source excerpts and construct written responses to open ended questions about these sources. The responses are often brief, a paragraph or two, and must contain evidence extracted from the sources. This is a process that is elegantly simple and focused on historical thinking skills.

No Stated Learning Objectives

As I've pointed out in some of my tweets, I think it is significant that the authors do not include a list of learning objectives. This stands out to me because it is contrary to the model of lesson planning that I was taught, and I am sure many of you were also, when taking education classes (pdf). I accept that there is more than one way to lesson plan, though I have rarely observed models that do not include learning objectives.

In fact, a style of lesson planning that purposely excludes defining learning objectives is, in my opinion, quite provocative and sending a clear and powerful message about one of its prime assumptions about teaching and learning.

The assumption that I detect is that it is not necessary for a teacher to state in precise language measurable statements about what a student will, and by implication, will not learn in a lesson. It is enough to base your lesson on a quality process and some meaningful content.

The SHEG model's quality process is, at its core, a genuine commitment to having students close read primary and secondary source excerpts and construct written responses to open ended questions about these sources. The responses are often brief, a paragraph or two, and must contain evidence extracted from the sources. This is a process that is elegantly simple and focused on historical thinking skills.

Tuesday, August 13, 2013

Sample Text on Trial Assignment: Writing a Brief- Thomas Hobbes (+ some personal reflection at end)

Thomas Hobbes receives all of 2 paragraphs in our textbook, which is in step with one of the text's most common biases, lack of substance. As we've discussed, for source work to be productive and thoughtful, you must approach the sources with questions. Accordingly, your job is to prepare questions in advance of your analysis of some of Hobbes' writings. Your 'interview' with Hobbes will begin the process of adding to and supporting the textbook's thin account of him.

Start by reading what is in the text about Hobbes. With another history detective, create a brief discussing your reading of the text and the questions you have generated.

Sample 'Brief'

In one of the text's introductory paragraphs, the author states that the Enlightenment "started from some key ideas put forth by two English political thinkers of the 1600s, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke." The implication, it appears to me, is that these two individuals were solely responsible for birthing the intellectual movement that historians refer to as the Enlightenment. Such a narrow view of causation, I think, warrants tremendous scrutiny.

I was unable to find a visual of Hobbes in our text. I checked the textbook's index, discovering that he is also mentioned in a single paragraph on page 22, as is John Locke. The text discusses one of Hobbes' writings called Leviathan (1651). The language in the text almost makes it sound as if Hobbes has no other writings. I doubt that this is the case. Hobbes is partially quoted twice in the two paragraphs. The book also states some of his assertions about government, human nature, and life in a so called 'state of nature'. Here are the questions that I am going to begin my source work with:

1. How many other works, besides Leviathan, did Hobbes write?

2. The text mentions no biographical details about Hobbes other than that he lived in England during the English Civil War. What are some other details about Hobbes life? The textbook is little help here, presenting him one dimensionally.

3. Did Hobbes really believe, as our text states, that all people were naturally selfish and wicked? Why did he believe this?

4. What thinkers influenced Hobbes? The text fails to place Hobbes into an immediate context. Who were his contemporaries? Who influenced him?

5. Was Hobbes the first to use the term state of nature?

6. Our text says that Hobbes believed that the best government was an absolute monarchy since it possessed the tremendous power that was required to keep people in order. Wouldn't an absolute monarchy, given its significant power, treat people poorly? Did Hobbes try to reconcile these two ideas? If so, how?

My Reflection

In the past, I have definitely looked at two paragraphs on Hobbes as content that students needed to be fed in preparation for a test. With a little effort, I am sure, I can find numerous powerpoint slides that I have created expressing ideas similar, if not identical, to the text about Hobbes. I am also sure that I can find a variety of worksheets containing questions that ask students to pull and copy these ideas from the text. About a half hour with me and the textbook, and this caricature of Hobbes, and we would move on, only to do the same with the next figure in the text, Locke, and the one that follows him, Voltaire.

The change in my teaching that I am looking to initiate involves deliberately doing more than this.

In addition to exposing my students to more than just two paragraph accounts of important thinkers, I want them to grapple with some of the same issues and questions these thinkers wrote about.

This type of teaching doesn't have much room for powerpoints and worksheets. Indeed, it requires teachers who are comfortable planning learning experiences that rarely involve powerpoint and worksheets, teachers who possess patience, creativity, and curiosity, along with a willingness to model and support students as they learn complex and meaningful skills. Above all, this model of teaching requires a willingness to say textbook history is not enough. I refuse to treat the text as an end rather than a beginning.

Start by reading what is in the text about Hobbes. With another history detective, create a brief discussing your reading of the text and the questions you have generated.

Sample 'Brief'

In one of the text's introductory paragraphs, the author states that the Enlightenment "started from some key ideas put forth by two English political thinkers of the 1600s, Thomas Hobbes and John Locke." The implication, it appears to me, is that these two individuals were solely responsible for birthing the intellectual movement that historians refer to as the Enlightenment. Such a narrow view of causation, I think, warrants tremendous scrutiny.

I was unable to find a visual of Hobbes in our text. I checked the textbook's index, discovering that he is also mentioned in a single paragraph on page 22, as is John Locke. The text discusses one of Hobbes' writings called Leviathan (1651). The language in the text almost makes it sound as if Hobbes has no other writings. I doubt that this is the case. Hobbes is partially quoted twice in the two paragraphs. The book also states some of his assertions about government, human nature, and life in a so called 'state of nature'. Here are the questions that I am going to begin my source work with:

1. How many other works, besides Leviathan, did Hobbes write?

2. The text mentions no biographical details about Hobbes other than that he lived in England during the English Civil War. What are some other details about Hobbes life? The textbook is little help here, presenting him one dimensionally.

3. Did Hobbes really believe, as our text states, that all people were naturally selfish and wicked? Why did he believe this?

4. What thinkers influenced Hobbes? The text fails to place Hobbes into an immediate context. Who were his contemporaries? Who influenced him?

5. Was Hobbes the first to use the term state of nature?

6. Our text says that Hobbes believed that the best government was an absolute monarchy since it possessed the tremendous power that was required to keep people in order. Wouldn't an absolute monarchy, given its significant power, treat people poorly? Did Hobbes try to reconcile these two ideas? If so, how?

My Reflection

In the past, I have definitely looked at two paragraphs on Hobbes as content that students needed to be fed in preparation for a test. With a little effort, I am sure, I can find numerous powerpoint slides that I have created expressing ideas similar, if not identical, to the text about Hobbes. I am also sure that I can find a variety of worksheets containing questions that ask students to pull and copy these ideas from the text. About a half hour with me and the textbook, and this caricature of Hobbes, and we would move on, only to do the same with the next figure in the text, Locke, and the one that follows him, Voltaire.

The change in my teaching that I am looking to initiate involves deliberately doing more than this.

In addition to exposing my students to more than just two paragraph accounts of important thinkers, I want them to grapple with some of the same issues and questions these thinkers wrote about.

This type of teaching doesn't have much room for powerpoints and worksheets. Indeed, it requires teachers who are comfortable planning learning experiences that rarely involve powerpoint and worksheets, teachers who possess patience, creativity, and curiosity, along with a willingness to model and support students as they learn complex and meaningful skills. Above all, this model of teaching requires a willingness to say textbook history is not enough. I refuse to treat the text as an end rather than a beginning.

Monday, August 12, 2013

Sample Blog Assignment Sheet

During last night's #HSGovChat, I mentioned having my students blog. Here is an example of a blog assignment sheet that I might give them on a Monday. Assignment due dates are scattered during the week. When I have more time, I will discuss my experiences with having students blog. If you have any questions, experiences of your own, please share :)

Sunday, August 11, 2013

Planning, Standards, and Teaching for Understanding

When you sit down to 'plan a lesson', what goes through your head? In some of my posts this week, I want to unpack the idea of 'planning a lesson'. The idea that one person, a teacher, can deliberately direct another person, a student, to learn something is complicated enough. Multiply this complexity by the number of students we teach and all of a sudden planning a lesson seems next to impossible, yet we do it every day. How?

I often see a disconnect between the complex nature of teaching and learning and the casual way we talk about the two. To a degree, this makes sense. If we let this complexity silence us, what good would that do? After all, we are teachers. It is important that we talk, a lot, about teaching and learning. The label itself, teacher, suggests that we, more than most, have a firm grasp of the complexities associated with teaching and learning.

Given the inherent complexities associated with directing the learning of a classroom of twenty five or thirty students, how should we, as social studies teachers, think about the teaching and learning process?

To begin, we must consider what we are trying to teach. Obviously, the easy answer is that we are trying to teach our students the school's curriculum, which, hopefully, overlaps with state standards. Easy answers, though, are usually not the best answers. After all, one look at curriculum documents and state standards reveals that the language of these texts is often tremendously ambiguous. Here are some standards pulled from the state of Virginia:

Era VI: Age of Revolutions, 1650 to 1914 a.d. (c.e.)

What does it mean to describe the French Revolution? A narrow view of this standard suggests that students can simply state a few facts about the French Revolution and they have described it. A much broader view of this standard might include students spitting back tons of textbook and teacher presented facts about the French Revolution. Is this better than just a few facts? If so, why?

It appears, by the way that this standard is constructed/written, that if students are able to do (do?) a-f, whether narrowly or broadly, then they have demonstrated knowledge of scientific, political, economic, and religious changes during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. Should we be satisfied with this? And is it even reasonable to say that being able to do (what are students being asked to do?) items a-f = a knowledge of the aforementioned changes?

Virginia does include some language about historical thinking:

WHII.1 The student will improve skills in historical research and geographical analysis by

a) identifying, analyzing, and interpreting primary and secondary sources to make generalizations about events and life in world history since 1500 A.D. (C.E.);

I want to take a closer look at the released assessment questions to see how the state of Virginia tries to measure these standards. Do they measure the standards using a narrow or a broad interpretation? Regardless of the answer, how are teachers to know how the state will interpret these standards when writing assessment questions?

I often see a disconnect between the complex nature of teaching and learning and the casual way we talk about the two. To a degree, this makes sense. If we let this complexity silence us, what good would that do? After all, we are teachers. It is important that we talk, a lot, about teaching and learning. The label itself, teacher, suggests that we, more than most, have a firm grasp of the complexities associated with teaching and learning.

Given the inherent complexities associated with directing the learning of a classroom of twenty five or thirty students, how should we, as social studies teachers, think about the teaching and learning process?

To begin, we must consider what we are trying to teach. Obviously, the easy answer is that we are trying to teach our students the school's curriculum, which, hopefully, overlaps with state standards. Easy answers, though, are usually not the best answers. After all, one look at curriculum documents and state standards reveals that the language of these texts is often tremendously ambiguous. Here are some standards pulled from the state of Virginia:

Era VI: Age of Revolutions, 1650 to 1914 a.d. (c.e.)

WHII.6 The student

will demonstrate knowledge of scientific, political, economic, and religious

changes during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries by

a) describing the

Scientific Revolution and its effects;

b) describing the Age

of Absolutism, including the monarchies of Louis XIV and Peter the Great;

c) assessing the

impacts of the English Civil War and the Glorious Revolution on democracy;

d) explaining the

political, religious, and social ideas of the Enlightenment and the ways in

which they influenced the founders of the United States;

e) describing the

French Revolution;

f) describing the

expansion of the arts, philosophy, literature, and new technology.

What does it mean to describe the French Revolution? A narrow view of this standard suggests that students can simply state a few facts about the French Revolution and they have described it. A much broader view of this standard might include students spitting back tons of textbook and teacher presented facts about the French Revolution. Is this better than just a few facts? If so, why?

It appears, by the way that this standard is constructed/written, that if students are able to do (do?) a-f, whether narrowly or broadly, then they have demonstrated knowledge of scientific, political, economic, and religious changes during the sixteenth, seventeenth, and eighteenth centuries. Should we be satisfied with this? And is it even reasonable to say that being able to do (what are students being asked to do?) items a-f = a knowledge of the aforementioned changes?

Virginia does include some language about historical thinking:

WHII.1 The student will improve skills in historical research and geographical analysis by

a) identifying, analyzing, and interpreting primary and secondary sources to make generalizations about events and life in world history since 1500 A.D. (C.E.);

In practice, I suspect, many teachers will toss in a few primary sources and feel satisfied with the results. And it appears, according to the state standards, they have done their job. I want to take a closer look at the released assessment questions to see how the state of Virginia tries to measure these standards. Do they measure the standards using a narrow or a broad interpretation? Regardless of the answer, how are teachers to know how the state will interpret these standards when writing assessment questions?

Saturday, August 10, 2013

Text on Trial: The Charge- A 1 Dimensional Presentation of an Individual

Textbooks are notorious for briefly mentioning individuals from the past, providing a few basic facts, and moving on. In this discovery, we are going to examine how our textbook treats Nicholas Copernicus.

Here are some questions that can be used to structure student inquiry. I have provided some answers to better illustrate this approach/model.

Is the person mentioned in the index? Copernicus is mentioned. He is on one page.

Does the text provide a visual of this person ? Also, are there visuals associated with this person's actions/ideas?

Yes, there is a painting of Copernicus on page 168.

If there is/are visual(s), discuss them? What stands out?

There is painting showing Copernicus standing in front of a globe like structure. The source of the work is not given, something we have previously noted this text does. I did, however, find a section in the back of the text that provides brief info about all of the art in the book. The image is apparently from the Granger Collection. A quick search of the collection revealed the picture in the text, stating "After the painting by Otto Brausewetter." (1835-1904). I was unable to discover biographical info about the artist.

After reading how the textbook treats this individual, what stands out?

The text discusses Copernicus in three paragraphs. None of Copernicus' own words are used in the text, no excerpts from his writings. There is no attempt to connect Copernicus to his contemporaries, suggesting little context for him becoming "interested in an old Greek idea that the sun stood at the center of the universe."

The text mentions that Copernicus feared "ridicule or persecution", but how this is known is not explored. It is mentioned that he did not publish his work until 1543, receiving a copy of it on his deathbed (true?).

Does the text connect this individual to a larger historical context?

No. (My interjection: The omission of a reference to the Protestant Reformation is glaring.)

What are your next moves? What topics associated with this person are you interested in researching further? Explain what and why.

I would like to learn more about Copernicus' fears of "ridicule and persecution". How did he express these fears? I would also like to explore further other scientists who lived during Copernicus' time that may have been exploring topics and making discoveries that threatened the Church.

Here are some questions that can be used to structure student inquiry. I have provided some answers to better illustrate this approach/model.

Is the person mentioned in the index? Copernicus is mentioned. He is on one page.

Does the text provide a visual of this person ? Also, are there visuals associated with this person's actions/ideas?

Yes, there is a painting of Copernicus on page 168.

If there is/are visual(s), discuss them? What stands out?

There is painting showing Copernicus standing in front of a globe like structure. The source of the work is not given, something we have previously noted this text does. I did, however, find a section in the back of the text that provides brief info about all of the art in the book. The image is apparently from the Granger Collection. A quick search of the collection revealed the picture in the text, stating "After the painting by Otto Brausewetter." (1835-1904). I was unable to discover biographical info about the artist.

After reading how the textbook treats this individual, what stands out?

The text discusses Copernicus in three paragraphs. None of Copernicus' own words are used in the text, no excerpts from his writings. There is no attempt to connect Copernicus to his contemporaries, suggesting little context for him becoming "interested in an old Greek idea that the sun stood at the center of the universe."

The text mentions that Copernicus feared "ridicule or persecution", but how this is known is not explored. It is mentioned that he did not publish his work until 1543, receiving a copy of it on his deathbed (true?).

Does the text connect this individual to a larger historical context?

No. (My interjection: The omission of a reference to the Protestant Reformation is glaring.)

What are your next moves? What topics associated with this person are you interested in researching further? Explain what and why.

I would like to learn more about Copernicus' fears of "ridicule and persecution". How did he express these fears? I would also like to explore further other scientists who lived during Copernicus' time that may have been exploring topics and making discoveries that threatened the Church.

Friday, August 9, 2013

Meaningful Question + Inquiry (Tools/Opportunities to Learn) = Meaningful Learning

Quoting Nebraska's History Teacher of the Year, Sarah Winans: "Critical thinking is cultivated when a meaningful question is posed, and students are given the tools and opportunities to engage in inquiry through texts of varying perspective." Read more here.

Text on Trial: An Example of an Assignment

Historical Detectives: Please read the text passage below, paying close attention not only to its message about the past but also to how this message is conveyed to readers: What is said? How is it said? Also, what is not said?

Quoting from page 165 of our textbook- Modern World History: Patterns of Interaction: "A combination of discoveries and circumstances led to the Scientific Revolution and helped spread its impact. By the late Middle Ages, European scholars had translated many works by Muslim scholars. These scholars had compiled a storehouse of ancient and current scientific knowledge. Based on this knowledge, medieval universities added scientific courses in astronomy, physics, and mathematics."

1. What is said? Are there words or references used that strike you as imprecise, vague?

Possible responses include the following:

-"late Middle Ages"- When is this?

-"European scholars"- Names?

-"Muslim scholars"- Names?

-"medieval universities"- Which ones?

2. What other questions does this selection prompt you to ask?

Possible responses include:

How, and under what circumstances, did Muslim scholars "compile a storehouse of ancient and current scientific knowledge"?

Who attended medieval universities? What were some of the prominent ones?

3. What kinds of textbook biases did you detect in this passage? Are there any new kinds of biases detected?

Possible response

I definitely noticed the bias of the general over the specific, as well as a bias against giving specific examples: an example, or an excerpt, of a text that was preserved by Muslim scholars could be provided. Also, the textbook has a habit of just dropping huge events on us with little or no context. Where did these Muslim scholars come from? I wonder if they were mentioned previously in the book.

4. What are your next moves? If you were going to improve this passage, bringing it up to our standards, what topic(s) do you need to research further? Once you conduct your research, I'd like you to submit a revised (and sourced) draft of this passage to our editors. As always, you may conduct your research with another detective, but remember to keep me in the loop.

Quoting from page 165 of our textbook- Modern World History: Patterns of Interaction: "A combination of discoveries and circumstances led to the Scientific Revolution and helped spread its impact. By the late Middle Ages, European scholars had translated many works by Muslim scholars. These scholars had compiled a storehouse of ancient and current scientific knowledge. Based on this knowledge, medieval universities added scientific courses in astronomy, physics, and mathematics."

1. What is said? Are there words or references used that strike you as imprecise, vague?

Possible responses include the following:

-"late Middle Ages"- When is this?

-"European scholars"- Names?

-"Muslim scholars"- Names?

-"medieval universities"- Which ones?

2. What other questions does this selection prompt you to ask?

Possible responses include:

How, and under what circumstances, did Muslim scholars "compile a storehouse of ancient and current scientific knowledge"?

Who attended medieval universities? What were some of the prominent ones?

3. What kinds of textbook biases did you detect in this passage? Are there any new kinds of biases detected?

Possible response

I definitely noticed the bias of the general over the specific, as well as a bias against giving specific examples: an example, or an excerpt, of a text that was preserved by Muslim scholars could be provided. Also, the textbook has a habit of just dropping huge events on us with little or no context. Where did these Muslim scholars come from? I wonder if they were mentioned previously in the book.

4. What are your next moves? If you were going to improve this passage, bringing it up to our standards, what topic(s) do you need to research further? Once you conduct your research, I'd like you to submit a revised (and sourced) draft of this passage to our editors. As always, you may conduct your research with another detective, but remember to keep me in the loop.

Text on Trial: Voices Not Heard

I read an article yesterday by Joyce Delaney called Voices Not Heard: Women in a History Textbook. As I think about my text on trial assignment, I, obviously, need to make sure that my students are noticing how women are treated by the authors. How frequently are women mentioned? When women are mentioned, what kind of language is used? In addition to what words are used, what words are not used?

The author states the following powerful and revealing question posed to a group of high school seniors: In five minutes or less, can you name "twenty famous American women, past or present, excluding sports or entertainment figures?" The average student names four or five women. Why is this the case? The author and the teachers who posed the question point to textbooks. Students know so few women, they argue, "because their books tell them little".

The author states the following powerful and revealing question posed to a group of high school seniors: In five minutes or less, can you name "twenty famous American women, past or present, excluding sports or entertainment figures?" The average student names four or five women. Why is this the case? The author and the teachers who posed the question point to textbooks. Students know so few women, they argue, "because their books tell them little".

Thursday, August 8, 2013

Text on Trial: "Launched a change in European thought"?

Passage from Text: "Beginning in the mid-1500s, a few scholars published works challenging the ideas of the ancient thinkers and the church. As these scholars replaced old assumptions with new theories, they launched a change in European thought that historians call the Scientific Revolution. The Scientific Revolution was a new way of thinking about the natural world. That way was based upon careful observation and a willingness to question accepted beliefs."

Discussion: Here is some language that immediately jumps out as problematic:

"Beginning in the mid-1500s"- Were no scholars challenging the ideas of ancient thinkers and the church before the mid 1500s?

"a few scholars"- Which ones? None are named.

"challenging the ideas of the ancient thinkers and the church"- Which ideas were challenged?

"these scholars...launched a change in European thought"- How does one launch a change in thought? What is "European thought"?

More work needs to be done here...

Discussion: Here is some language that immediately jumps out as problematic:

"Beginning in the mid-1500s"- Were no scholars challenging the ideas of ancient thinkers and the church before the mid 1500s?

"a few scholars"- Which ones? None are named.

"challenging the ideas of the ancient thinkers and the church"- Which ideas were challenged?

"these scholars...launched a change in European thought"- How does one launch a change in thought? What is "European thought"?

More work needs to be done here...

Text on Trial: Picture in Text without Reference to Source

Caption in Text= "Galileo tries to defend himself before the Inquisition. The Court, however, demands that he recant."

Discussion: This source states that the above painting is from the 19th century. And this source attributes the painting as follows: "Galileo before the Holy Office, a 19th century painting by Joseph-Nicolas Robert-Fleury."

Why is this a problem? The painting appears under a section titled Interact with History. The authors are attempting to show the reader what the trial may have looked liked. It is not stated that this work of art was created centuries after the trial, nor is any attempt made to discuss how art reveals information about the artist, the society and times he lived in, and his view of the past.

Text on Trial: Origins of Geocentric Theory

Our Textboook: "This earth centered view of the universe, called the geocentric theory, was supported by more than just common sense. The idea came from Aristotle, the Greek philosopher of the fourth century B.C."

"Ancient societies were obsessed with the idea that God must have placed humans at the center of the cosmos (a way of referring to the universe). An astronomer named Eudoxus created the first model of a geocentric universe around 380 B.C." Source: http://cmb.physics.wisc.edu/tutorial/briefhist.html

"Aristotle developed a more intricate geocentric model (which was later refined by Ptolemy), general cosmology clung to these misconstrued ideas for the next 2,000 years." Source: http://cmb.physics.wisc.edu/tutorial/briefhist.html

Discussion: Our class text states that the geocentric theory "came from Aristotle", ignoring anyone who may have influenced Galileo. This an offense of context as well as, potentially, of discovery.

An offense of context occurs when the text presents a topic with little of no background information. I suspect we will find these context offenses frequently.

Another source discusses Eudoxus: "Perhaps Eudoxus’s greatest fame stems from his being the first to attempt, in On Speeds, a geometric model of the motions of the Sun, the Moon, and the five planets known in antiquity. His model consisted of a complex system of 27 interconnected, geo-concentric spheres, one for the fixed stars, four for each planet, and three each for the Sun and Moon. Callippus and later Aristotle modified the model. Aristotle’s endorsement of its basic principles guaranteed an enduring interest through the Renaissance."

Note: More research needs to be done. I am suggesting, however, that stating "the idea came from Aristotle" demands further investigation.

Here is a link to a version of Aristotle's On the Heavens, as well as a Wikipedia overview of the text.

Aristotle begins to discuss the earth in Book II, Part13. (Book II, Part 13 in a google doc )

"Ancient societies were obsessed with the idea that God must have placed humans at the center of the cosmos (a way of referring to the universe). An astronomer named Eudoxus created the first model of a geocentric universe around 380 B.C." Source: http://cmb.physics.wisc.edu/tutorial/briefhist.html

"Aristotle developed a more intricate geocentric model (which was later refined by Ptolemy), general cosmology clung to these misconstrued ideas for the next 2,000 years." Source: http://cmb.physics.wisc.edu/tutorial/briefhist.html

Discussion: Our class text states that the geocentric theory "came from Aristotle", ignoring anyone who may have influenced Galileo. This an offense of context as well as, potentially, of discovery.

An offense of context occurs when the text presents a topic with little of no background information. I suspect we will find these context offenses frequently.

Another source discusses Eudoxus: "Perhaps Eudoxus’s greatest fame stems from his being the first to attempt, in On Speeds, a geometric model of the motions of the Sun, the Moon, and the five planets known in antiquity. His model consisted of a complex system of 27 interconnected, geo-concentric spheres, one for the fixed stars, four for each planet, and three each for the Sun and Moon. Callippus and later Aristotle modified the model. Aristotle’s endorsement of its basic principles guaranteed an enduring interest through the Renaissance."

Note: More research needs to be done. I am suggesting, however, that stating "the idea came from Aristotle" demands further investigation.

Here is a link to a version of Aristotle's On the Heavens, as well as a Wikipedia overview of the text.

Aristotle begins to discuss the earth in Book II, Part13. (Book II, Part 13 in a google doc )

Wednesday, August 7, 2013

Draft of #HSGovChat Questions for Sunday 8/11

1. How do you define inquiry learning? What is it/what isn't it?

2. Why is student inquiry particularly valuable in a government class?

3. In your government class, when do students engage in inquiry learning?

4. What are some challenges/obstacles associated with having students learn via inquiry?

5. Given the open ended nature of inquiry, what are some ways to manage it without stifling student exploration?

6. What are some resources you have used to create inquiry lessons in your government class?

7. What are some inquiry lessons, activities you would like to share with others?

2. Why is student inquiry particularly valuable in a government class?

3. In your government class, when do students engage in inquiry learning?

4. What are some challenges/obstacles associated with having students learn via inquiry?

5. Given the open ended nature of inquiry, what are some ways to manage it without stifling student exploration?

6. What are some resources you have used to create inquiry lessons in your government class?

7. What are some inquiry lessons, activities you would like to share with others?

Textbook on Trial: The Charges and Getting Started

The charges: How will I get this started? (yesterday's post)

I am thinking I will need to spend some time exploring with students what they already know about our adversarial system of criminal justice. An easy way to initiate this discussion is with the following question: What is the difference between being "innocent until proven guilty" vs. "guilty until proven innocent"? This question provides an opportunity to discuss the idea of burden of proof, which means it is up to the prosecution to prove to a jury that the defendant is guilty of the charges he is being accused of.

Now explain to students how this semester we will be using the idea or framework of a trial to learn more about history and how history is created. Throughout the course we are going to be putting our textbook on trial. It is the prosecution's contention that the authors of our textbook are guilty of the following "crimes of reason" (might try a different phrase):

-overgeneralizing

-errors of omission

-providing simplistic accounts

-supporting assertions about the past with little or no evidence

-providing little or no context about a past event

(Some of these charges overlap. Are these enough? Are there others you would add?)

Need to Consider

To conduct a trial there needs to be laws, law enforcement, as well as the following actors: prosecution, defense, judge, jury.

All involved need to understand the law. To make sure that my students understand the laws I listed above, I will need to spend time elaborating, developing these laws. (Thinking of adding to our "legal code", if you will, a series of logical fallacies.)

Also, notice how none of the charges say that the authors are lying outright. I think sometimes teachers and students think that this is the only way that textbooks distort the past. Through this assignment we will often explore, I suspect, more nuanced ways that distortions of the past occur.

Initial Exploration of the Text

I want to spend time with the textbook, so that I can think about ways students will interact with it. At this point, I will likely be all over the place in my planning, trying to get a feel for all of the moving parts.

For this reading of the text, I want you to imagine that you are in the prosecutor's office. We need to spend some time organizing our case, which requires us to think about the law as we carefully read the text.

Have students turn to page 165 in our Modern World History textbook. Already, by providing students with the "mentality of a lawyer" (of a critical reader) you will have changed dramatically how they approach the text.

I will likely work through this page of the textbook with students. This will give me a chance to talk about how textbooks are written and what we should be looking for.

Page 165 begins with a "Setting the Stage" paragraph. This is an introduction to the section of the text we are reading, which is called the Scientific Revolution.

When writing an intro, an author is preparing the reader for what is to come later in the text. It is ok and accepted that a writer will be general in this opening paragraph.

Under "Setting the Stage" is a bold heading in red: The Roots of Modern Science. Again, we will often find an introductory paragraph under such headings. As critical readers, it is important that we use these headings. In many ways, these headings cue the reader about what they can expect to learn from this section of the text. The author is telling the reader that the proceeding paragraphs will address the following question: What are the roots of modern science? (Talk about turning the section heading into a question)

Point out to students that it is after the introductory paragraph that we will be strictly holding the author to the rules of reason. This is where we, as prosecutors, are going to find violations.

There are two smaller green headings: The 'Medieval View' and 'A New Way of Thinking'. The Medieval View only gets two paragraphs. This is a red flag since it is quite difficult to deal with topics in a careful, thoughtful way in just two paragraphs.

The first paragraph is 5 sentences: "During the Middle Ages, most scholars believed that the earth was an unmoving object located at the center of the universe. According to that belief, the moon, the sun, and the planets all moved in perfectly circular paths around the earth. Beyond the planets lay a sphere of fixed stars, with heaven still farther beyond. Common sense seemed to support this view. After all, the sun appeared to be moving around the earth as it rose in the morning and set in the evening."

And here is the second and final paragraph of this section. It is also 5 sentences: "This earth centered view of the universe, called the geocentric theory, was supported by more than just common sense. The idea came from Aristotle, the Greek philosopher of the fourth century B.C. The Greek astronomer Ptolemy expanded the theory in the second century A.D. In addition, Christianity taught that God had deliberately placed earth at the center of the universe. Earth was thus a special place on which the great drama of life took place."

What problems do we detect in these two paragraphs?

Paragraph 1

-When was the Middle Ages? Where does this term come from? (The defense will likely look for references to this term in previous sections of the text. Is the term used previously?)

-"most scholars believed that the earth was an unmoving object": Were there some who did not? That is how this phrase reads. If so, who?

-"the idea came from Aristotle": Is this accurate? Aristotle was the first to come up with geocentric theory? This, I think, is a question we need to explore deeper.

"Beyond the planets lay a sphere of fixed stars, with heaven still farther beyond." A visual would be helpful here. Any art/drawings from these periods that the author could have used?

More to come...

What are your thoughts? ideas?

I am thinking I will need to spend some time exploring with students what they already know about our adversarial system of criminal justice. An easy way to initiate this discussion is with the following question: What is the difference between being "innocent until proven guilty" vs. "guilty until proven innocent"? This question provides an opportunity to discuss the idea of burden of proof, which means it is up to the prosecution to prove to a jury that the defendant is guilty of the charges he is being accused of.

Now explain to students how this semester we will be using the idea or framework of a trial to learn more about history and how history is created. Throughout the course we are going to be putting our textbook on trial. It is the prosecution's contention that the authors of our textbook are guilty of the following "crimes of reason" (might try a different phrase):

-overgeneralizing

-errors of omission

-providing simplistic accounts

-supporting assertions about the past with little or no evidence

-providing little or no context about a past event

(Some of these charges overlap. Are these enough? Are there others you would add?)

Need to Consider

To conduct a trial there needs to be laws, law enforcement, as well as the following actors: prosecution, defense, judge, jury.

All involved need to understand the law. To make sure that my students understand the laws I listed above, I will need to spend time elaborating, developing these laws. (Thinking of adding to our "legal code", if you will, a series of logical fallacies.)

Also, notice how none of the charges say that the authors are lying outright. I think sometimes teachers and students think that this is the only way that textbooks distort the past. Through this assignment we will often explore, I suspect, more nuanced ways that distortions of the past occur.

Initial Exploration of the Text

I want to spend time with the textbook, so that I can think about ways students will interact with it. At this point, I will likely be all over the place in my planning, trying to get a feel for all of the moving parts.

For this reading of the text, I want you to imagine that you are in the prosecutor's office. We need to spend some time organizing our case, which requires us to think about the law as we carefully read the text.

Have students turn to page 165 in our Modern World History textbook. Already, by providing students with the "mentality of a lawyer" (of a critical reader) you will have changed dramatically how they approach the text.

I will likely work through this page of the textbook with students. This will give me a chance to talk about how textbooks are written and what we should be looking for.

Page 165 begins with a "Setting the Stage" paragraph. This is an introduction to the section of the text we are reading, which is called the Scientific Revolution.

When writing an intro, an author is preparing the reader for what is to come later in the text. It is ok and accepted that a writer will be general in this opening paragraph.

Under "Setting the Stage" is a bold heading in red: The Roots of Modern Science. Again, we will often find an introductory paragraph under such headings. As critical readers, it is important that we use these headings. In many ways, these headings cue the reader about what they can expect to learn from this section of the text. The author is telling the reader that the proceeding paragraphs will address the following question: What are the roots of modern science? (Talk about turning the section heading into a question)

Point out to students that it is after the introductory paragraph that we will be strictly holding the author to the rules of reason. This is where we, as prosecutors, are going to find violations.

There are two smaller green headings: The 'Medieval View' and 'A New Way of Thinking'. The Medieval View only gets two paragraphs. This is a red flag since it is quite difficult to deal with topics in a careful, thoughtful way in just two paragraphs.

The first paragraph is 5 sentences: "During the Middle Ages, most scholars believed that the earth was an unmoving object located at the center of the universe. According to that belief, the moon, the sun, and the planets all moved in perfectly circular paths around the earth. Beyond the planets lay a sphere of fixed stars, with heaven still farther beyond. Common sense seemed to support this view. After all, the sun appeared to be moving around the earth as it rose in the morning and set in the evening."

And here is the second and final paragraph of this section. It is also 5 sentences: "This earth centered view of the universe, called the geocentric theory, was supported by more than just common sense. The idea came from Aristotle, the Greek philosopher of the fourth century B.C. The Greek astronomer Ptolemy expanded the theory in the second century A.D. In addition, Christianity taught that God had deliberately placed earth at the center of the universe. Earth was thus a special place on which the great drama of life took place."

What problems do we detect in these two paragraphs?

Paragraph 1

-When was the Middle Ages? Where does this term come from? (The defense will likely look for references to this term in previous sections of the text. Is the term used previously?)

-"most scholars believed that the earth was an unmoving object": Were there some who did not? That is how this phrase reads. If so, who?

-"the idea came from Aristotle": Is this accurate? Aristotle was the first to come up with geocentric theory? This, I think, is a question we need to explore deeper.

"Beyond the planets lay a sphere of fixed stars, with heaven still farther beyond." A visual would be helpful here. Any art/drawings from these periods that the author could have used?

More to come...

What are your thoughts? ideas?

Tuesday, August 6, 2013

Textbook on Trial: Some opening thoughts

The idea of having my students put our class textbook on trial came to me earlier this summer. My wife was in the middle of watching the George Zimmerman trial, and I was in the midst of reading and tweeting about historical thinking skills.

What I was doing and what my wife was doing started to merge, to the point where I could not help but notice the similarities between what lawyers do and what historians do.

I am obviously not the first to recognize that the thinking skills, habits, and attitudes of mind often internalized and utilized by lawyers, at times at least, bear close resemblance to how historians think, how they approach evidence, and how they construct interpretations about the past.

Indeed, the structure and procedures of the American legal system, which is adversarial in nature, also resemble, in ways, how historians handle evidence, construct arguments, and, ultimately, prove their case to readers.

It is understandable, yet disheartening, that these similarities may go unnoticed. Anecdotally, and more formally, it has been well established that many students and teachers associate learning history with memorizing facts. Often, these crammed facts are then regurgitated on tests in the form of written responses and dozens of multiple choice and true/false items. The facts are then forgotten so that the next test can be conquered. This is a dance that occurs in too many classrooms.

The gap between what historians do and how history is taught in schools is often wide. Some of the differences are justified; many are not.

This assignment, which I currently imagine as ongoing and semester long, will attempt to decrease this chasm by deliberately highlighting the parallels mentioned above and below. Specifically, I will use an adversarial framework to teach my students how to think like a lawyer and an historian as they put their history textbook on trial.

Here is a quick list of some of the thinking skills this assignment will emphasize:

-Asking questions of sources

-Identifying and questioning facts

-Speculating about physical evidence

-Considering the benefits and problems associated with eyewitness accounts

-Creating a narrative that conforms to (is supported by) the facts (Making the facts conform to a narrative structure, making disparate pieces of evidence fit together, like putting together a puzzle without all of the pieces. Also, noticing when this is done and pointing where and how it was done)

-Identifying and making inferences

-Corroborating stories/accounts of the past

-Critically examining accounts of the past (questioning these accounts,handling conflicting accounts of the same event,understanding and explaining why accounts of past events may differ)

-Deciding when we can express confidence or when we should be skeptical about our ability to "know what happened" in the past

-Establishing context to understand past events

-Establishing context to construct accounts of the past

Some caveats

Teacher who rely solely on textbooks to teach history considerably limit their students' awareness of the dynamic and sophisticated nature of the discipline of history. Though some of you may disagree, I am comfortable saying that textbooks have a place in a history classroom.

At the same time, if my child ended up in a history class with a teacher who did not use a textbook, I would be less concerned than if they ended up in a class where on a daily basis the teacher taught directly from a textbook.

Finally, to a large degree, my idea is a gimmick, a way of imposing certain attitudes and expectations on my students from day 1 of my class. I do not envision this structure to follow a mock trial format. In the coming days, I will attempt to get more specific, elaborating and refining as I go.

Your thoughts? I encourage (and need!) comments, reactions, questions, ideas... Thanks :)

Monday, August 5, 2013

Information Overload and How to Cope

Last night I spent an hour tweeting with government teachers from around the country (world?). As Twitter teacher discussions often are, it was fast paced, stimulating, and tiring! Twitter is to professional development what a high def cable tv is to the old rabbit eared models. And to think, if I had not become active on Twitter this year, I would have likely gone the whole summer not talking to a single teacher. Those days are over.

In fact, the days of me yearning to talk teaching with a variety of other teachers are over. I can now do that with ease. As I mentioned during last night's discussion, there are taboos, unwritten rules, against being too chatty during the school day. Most teachers, including myself, are often busy grading and prepping for the next day to be genuinely open to impromptu reflective conversations about our craft.

To address this, principals will often mandate monthly department meetings, where some time is spent with colleagues talking about what we teach (curriculum), how we assess (formal and informal tests), and, occasionally, how we teach (methods). The results of these planned curricular meetings are often concrete by design; a test is made or an exam might be reviewed and revised. During these planned meetings, open ended Socratic style reflection and dialogue about the nature of teaching and learning is often seen as inefficient and, in my experience, discouraged.

Anyway, back to my summer work. This summer I have read dozens of journal articles about education, with a particular focus on history teaching, student inquiry, and the use of primary sources in the classroom. While reading, instead of writing notes in a copybook for my eyes only, I tweeted about them. And teachers responded.

At first, responses were occasional. In a short time, however, the responses I received and the connections I made increased exponentially. Indeed, this summer I learned how to use technology, especially Twitter, to create a virtual graduate school, a place I can go when I am interested in growing as a teacher and a learner. Twitter is a place I can go to ponder and reflect, where the only taboo is using too many characters!

Today, we are lucky to have such easy access to information and to each other. Having virtually unlimited access to so many resources is intellectually intoxicating and, at times, mind numbing.

I have come to realize that in order for me to truly benefit from these resources, I must consciously build time into my day to disconnect and reflect. Cognitive digestion, if you will. Writing on this blog is one way that I slow down and try to integrate new resources, ideas, and questions with my existing knowledge and skills.

Yesterday, I was reminded of the importance of regular reflection and processing time when I read something that I had read a few weeks prior. As I was reading this text again, I realized that in many ways it was like I was reading it for the first time. I had read it earlier this summer, but I had not reflected enough on the author's central message for his core ideas to become part of me.

Regular reflection and writing helps you to articulate your philosophy of teaching and learning. I see my philosophy as a core set of ideas that I use to filter and process new ideas and perspectives.

We all have a philosophy, whether we can easily state it or not. And the best way, in my opinion, to benefit from the amazing access to resources that we have today is to spend lots of time bringing your philosophy to the surface by writing about it and the new resources you encounter.

Only then will you be able to intelligently respond and grow. Do you blog about education? Why? Please let us know by leaving a comment and link below.

Sunday, August 4, 2013

Setup: Youtube to MP4 to Dropbox

Saturday, August 3, 2013

More on Mazur's Approach

What is it

that Mazur does? Mazur switched his approach from a straight lecture, where he

told students what they should know, to the following format: teacher asks a

question/poses a problem, students answer individually, students then discuss

their answer with person next to them, students then share answers+questions with teacher/teacher responds. Process repeats.

What might

this look like?

Traditional

Approach: Teacher stands in front of powerpoint slide on screen and tells

students some basic facts about Galileo. Students listen and copy some notes.

Teacher moves to next slide.

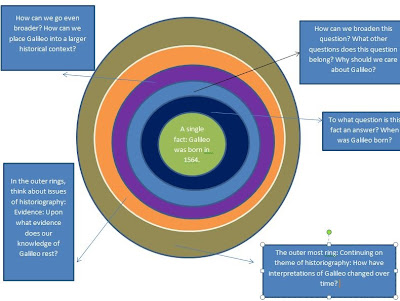

Alternative

Approach: Teacher shows students the following visual.

Tell students to write in their journal for 1-2 mins, noting as many

observations/questions as they can think of about this image.

For the next

3-4 mins, have students share their observations/questions with the person next

to them.

The teacher

can then randomly call on some students to have them share some of their, or

their partners, observations and questions. The teacher can also simply ask students to volunteer comments and questions.

This approach is so powerful because it dramatically shifts the role of students from passive information receivers to active creators of meaning.

This approach is so powerful because it dramatically shifts the role of students from passive information receivers to active creators of meaning.

Science in the News

Central

Question: What current stories about science capture your attention?

Length of

this investigation: 1 class period (Could also be assigned for HW)

Purpose: This

activity is designed to get you thinking about the following question: What is

science? I want students to see that science is all around them.

At this

point in Western Civ, students will be investigating the origins of science

(Here is an NPR story discussing the origins of the term scientist).

Setup: Ask class- When you think of the word

science, what do you think of? When and why do you think science began? How do

you define science?

Procedure

1. Find and read a story in the news that interests you.

The story should discuss science/a scientific investigation.

2. Post a link of the story to our Edmodo page (or

Twitter feed) + a brief description of why your classmates should read this

story.

3. Be prepared in class to summarize the story you read

and to discuss what interests you about this story?

Extension: It might be useful for students to

investigate the antecedents to the stories/topics they selected. This will help

students to see the incremental and collaborative nature of science.

Friday, August 2, 2013

Starting My Western Civ Course

What do Students Come in Knowing?

Today I was chatting with someone on Twitter about my Western Civ course. I mentioned that I was considering dropping my superficial attempts to prepare students for the start of my class, which begins in 16th century Europe. Usually, I will try to 'bring them up to speed', connecting the start of my course to history that they have previously studied. This usually does not feel like an effective way to start my course.

Seventh grade was the last time my students studied European history. In eighth grade, they study American history, ending around the 1920s. They'll pick up US history again in eleventh grade. And they'll study World history in tenth, after finishing Western Civ in ninth.

It does not seem worth using direct instruction if I am going to use it as a quick refresher of history they either covered quickly in seventh grade, or possibly never got to.

Superficially covering material is not meaningful teaching. It seems more reasonable to have students explore material previously covered (or never covered) when the need arises, when inquiry demands it.

Outline of my Western Civ Course: 90/90 minute blocks (content is mandated by district curriculum)

Intro: What is history? Why do people study the past?- 2 days (2)

Sci Rev-6 days (8)

Enlightenment- 6 days (14)

French Rev 10 days (24)

Napoleon and Congress of Vienna 6 days (30)

Industrial Rev 6 days (36)

Unification of Italy 3 days (39)

Unification of Germany 3 days (42)

European Imperialism 4 days (46)

World War I 10 days (56)

Russian Revolution 4 days (60)

Between the Wars 10 days (70)

World War

II 10 days (80)

Cold War 5 (85)

85 days out of 90

Subscribe to:

Comments (Atom)