Overview/Some Commentary

The mentality that we need to help students learn to avoid is just accepting a source at face value. This, I am reminded repeatedly, is the default mentality for most students and, I suspect, many adults, as well.

How do we do this? We do this by reminding students that since all primary and secondary sources are created by people, they need to viewed with an eye for the creator’s point of view and goals, both of which exist in a specific context. (Note: Historian Keith Barton reminds us that not all sources provide testimony. And because all sources DO NOT provide testimony, a simple sourcing heuristic is not always helpful. Issues of reliability and credibility are, obviously, most relevant when we are reading sources created for the purpose of transmitting a message and meaning, such as a letter or speech. Once a source's authenticity has been established, issues of credibility are NOT relevant when an historian is using evidence from the time period that does not provide testimony, such as receipts, newspaper ads, or government statistics...(make sense? I may need to review Barton and revise this section.))

What do students who DO NOT grasp the ideas and skills associated with sourcing tend to do?

A basic or novice understanding of sourcing involves a reader approaching a source with the following in mind:

Bias = bad, Unbiased = Good

We need to create experiences that helps students move beyond these simplistic notions.

Novice views of Sourcing

-If the source expresses bias, it cannot be used. Therefore, the source should be discarded.

-It IS possible and desirable to find and use unbiased source. This, after all, students assume, is what historians spend most of their time trying to do, discovering 'the truth' by finding unbiased sources that reveal it.

-Textbooks are an excellent place to turn if one is looking for an unbiased source.

-Primary sources provide us with a direct window to the past (using SHEG Stanford’s rubric language here with ‘direct window to the past.’)

Understandings that we should help our students move toward.

Any time an historian encounters a source of information, they analyze it to decide if and how they may use it in an historical argument.

All of us, whether historians or not, need to think about and analyze where the information we encounter is coming from. Otherwise, we have no way to judge the best way to respond to that content.

When we source, we can be more confident that we have answers to the following questions: What are we to make of this source? What meanings can we derive and infer from this source? Is this source trustworthy? How do we make this judgment? What parts of this source should we reject and why? What parts of this source should we accept and why?

What did I do in the classroom?

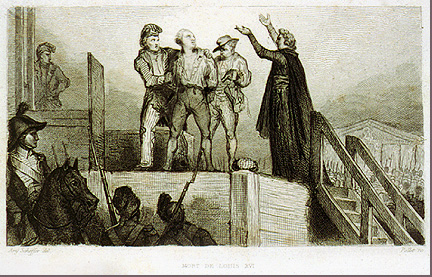

I set up this exercise using a source depicting Louis XVI’s execution. I was not able to determine the origin of this source. For the purpose of this assignment, I told students that we were going to assume it was created in 1830. Why did I have to give them a year? And why did I choose 1830? I knew that handing them a source and providing them with no information about who created it and when undermined the sourcing that I was going to have them do. I chose 1830 because I wanted to force students to think about the distance between the execution of Louis and the (supposed) creation of this source. What impact did over three decades have on how students interpreted this source?

How did I set this up?

Here are some questions that I used in class.

What is a source? (Some points to make/questions to ask: Are all sources the same? Should we treat a letter from a soldier to his wife differently than we might treat a collection of receipts or government statistics? If so, why? What's the difference?

Key point: A source is someone/something from which we get information. Students are often desensitized to the sources they encounter regularly, especially textbooks and teachers. Student desensitization is evident when their default is to accept information on face value that is provided by teachers and textbooks.)

Why is it important to question a source? (Some points to make/questions to ask: And what do we even mean by questioning a source? When we question a source, what kinds of questions should we ask? Some expected student responses to the importance of questioning a source:

So you can decide whether or not to believe the information.

So you can evaluate how accurate the information is.

(What are some points that I ought to make at this point in the lesson? Or at some point in this lesson? A source can often tell us much more than it literally says. It can tell us about the time period being studied. We need to interrogate a source in order to arrive at some of the more subtle meanings and messages contained within a source. When we get information we need to think about how the messenger influences the message. Source work is conducted for a reason. When historians are working with sources, whether primary or secondary, it is because they are trying to answer certain questions about the past.

How did I transition to the activity?

Tell students that sourcing is the first step in historical analysis, in thinking like an historian (see Big Six: 47).

Some sourcing questions are straightforward.

When was this source written/created?

Who created it?

What was the creator’s point of view? How do we know?

The Big Six text discusses how sourcing questions can become more subtle, abstract, and inference based. The big idea here, I think, is that we need to take what we have learned via our sourcing questions and draw some inferences, make some educated predictions about the reliability and usefulness of the source.

Based on our sourcing questions and answers, we to consider the creator of the source’s agenda: their purpose, goal(s) and motivations. And we need to keep these factors in mind when making judgments about the source.

For example, just because Napoleon says something happened, doesn’t mean that it happened exactly as he says. Napoleon’s words, though, do reveal aspects of his personality and character. They also tell us about his world, what was going on around him. For this reason, once we identify and account for a source's main biases, we can use the source to support our arguments about the past.

How reliable is this source? It depends on the historical questions you are asking.

Questions of reliability need to be precisely stated. Reliability does not just exist out there, as a concept. Reliable how? If this source is being used to consider how artists at different moments in time have portrayed Louis’ execution, then this source is reliable, in as far as it tells us something about the time period when it was created. If this source is being considered as evidence of how Louis XVI acted in the moments leading up to his execution, then it may be less reliable, given (at least for the purpose of this assignment) that it was created thirty years after his execution.

How did students interpret this source?

Some students were quick to describe the image, an essential beginning step in analyzing a source. It is necessary, however, that we teach students that they need to do more than just describe what they read or what they see. They need to link these observations to larger questions and answers. When students do this, they are beginning to think like an historian.

Here are some student comments that I’d like to consider (I have more that I will add and comment on) as I think about my rubric (linked below) and historical thinking in general:

Some student comments describing the image, describing Louis.

“Louis looks depressed.”

“..he must be scared. He is about to die. He acted calm and collected.”

“He listened to all of the orders he was given.” (We need to push the student to tell us why he is saying this. Is this accurate? We cannot determine the accuracy of this from a single source.)

“It is a picture of Louis getting executed.” (Though true, a basic observation.)

More comments will be added...

Additional Comments/Thoughts

-Some students may not even attempt to ‘close view/read’ the source. We should be able to discern whether or not a student has taken the time to view the source, to make some observations. Some students may 'close view' the source and see things that are not actually there. It is important that our rubric accounts for both possibilities.

Link to my Rubric ( I need to spend more time thinking about and writing about how I used this rubric and how it may need some revision.)